This is a modified excerpt from the Chapter on Voting in Everything You Believe Is Wrong.

Why Do We Vote?

Why do we vote in official elections? Or indeed elections of any kind? Because there are disagreements. Why are the disagreements? For two main reasons. Let’s look at both closely.

REASON ONE: people have the same goals, but there is uncertainty in how to bring these outcomes about. There are disputes over paths, but not destinations.

REASON TWO: people have differing goals. One side one thing, the other the exact opposite (of course, there could be many sides, none the same, and each with a party). In national elections we often hear of the “shared” goal of “making a better country” or “ensuring out future”. Yet what these mean to each individual is subject to enormous and irreconcilable variance. There can be diametric opposites: people mean different things when using those same phrases.

Shared Goals

Suppose we want to choose one of two men to “lead” the country—or company, or whatever (the number of men vying for the position is largely irrelevant). The man who wins has the job to implement, or to manage or guide, or at least attempt to implement, a set of shared goals.

Even if all voters shared the same goals of the country (or company, or whatever), then there still might be uncertainty over which man is the best to implement them. Hence there is a vote to make a formal decision. The voters all come with different ideas about the best man, but the all share the goals, at least loosely.

Not every man up for election will put the same emphasis on each shared goal, but the “pool” of goals is the same.

When there are shared goals and only uncertainty about who is best, the voters who lose the election will be unhappy that their man lost. In their opinion the best chance for implementing the shared goals was lost. But they will be comforted knowing that their goals will still be sought. The winners and losers still share the desire to reach the same destination.

Little disharmony should result because of the election. The winners have no reason to belittle or distrust the losers. Everybody wants to get along. After all, the winners want the same thing as the losers; the only difference is that the losers think there was a better person to lead us to these same ends.

No Shared Goals

Next suppose there are no shared goals, but still only two options for leader (or a limited number of choices). Each man running for office shares goals only with his own supporters. Each side will still have uncertainty about whether their man can implement the goals only their side shares. But each side only has one choice to who this man is.

Here, whoever wins, there will be only unhappiness. The losers will be deeply unhappy with the results, because they know none of their goals will be sought—at best, their goals can only be reached accidentally.

Since the losers desire different goals than those belonging to the winning party, and voting has not provided them a means toward these goals, the losers will begin to distrust voting itself. For good reason. Voting has failed them.

Voting, from their perspective, provided the worst possible outcome. Voting gave the wrong answer. The winners will gloat and celebrate, because they know they will be moving toward the goals they desire, and away from the disliked, undesirable, or hated goals of the losers. The winners wanted nothing to do with the losers’ goals, which follows from supposing there are no shared goals.

There will be no reason for the winners to court the losers, and every reason for the winners to be suspicious about the post-vote behavior of the losers. The winners may, of course, try to re-educate the losers into desiring their (the winners’) goals. Some losers may lash out, not seeing any other solution.

Sore Winners

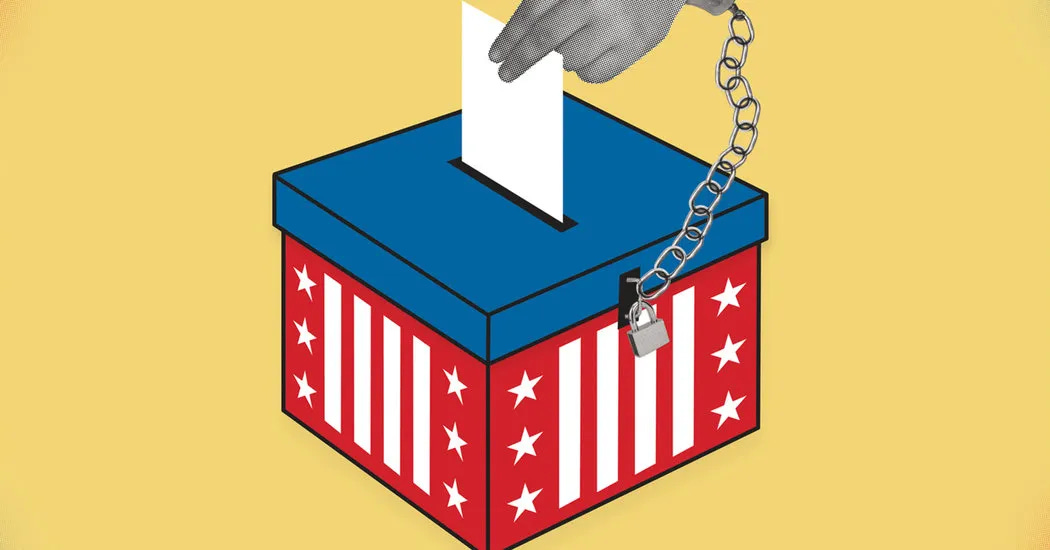

What’s even stranger when there are no shared goals, is that if the vote is close the winners will also distrust voting. Why shouldn’t they? Voting almost lost them their prize! They will say to themselves “Do we dare risk allowing a group of losers to vote and possibly be in the position of implementing their unwanted, disliked, or hated goals? Wouldn’t it be better to disallow voting altogether?” Voting hasn’t exactly failed, the winners think, but they now regard it with grave suspicion.

The Chapter goes on in this vein, about mixed shared goals, and the dissension caused by each side trying to convince the other their goals are best, all exacerbated by voting. Then comes the voting fortification.

Buy my new book and learn to argue against the regime: Everything You Believe Is Wrong.

I grew up and voted in West Viginia when it was blue and two governors went to jail; studied, worked and voted in Mayor Daley's Chicago where lots of city council members and three Illinois governors went to jail, was a DC lawyer when Bill Clinton was impeached, voted in Marion Barry's DC before he went to jail, lobbied Democrats in Congress for a living; vote in Don't it Make My Brown Eyes Blue Montgomery Couty Maryland, and hope to survive the nuclear consequences of the 2020 Steal.

I preternaturally distrust elections.

And for the sake of "our democracy," I favor stringent voter registration and ID laws, a voting age of 25, voting only by US citizens, leaving the Electoral College as is, and repealing the 17th Amendment.