Reader Chuck Lampert writes:

Hi Briggs! I got into a kerfluffle with some Climate Apocalypse true believers who said the frequency of 1/50, 1/100, 1/500, and 1/1000 yr floods is increasing because of climate change. Please correct me if I am wrong, but these intensity/frequency figure are almost entirely arbitrary and unless we have 1000’s if not millions of years of data are almost meaningless when applied to the 20th and 21st centuries only.

You are not in need of correction. There are no such things as 1/50, 1/100 and such like floods. Therefore, they cannot be increasing. Nor decreasing. They can't be anything.

The phrasing of the "hundred year flood" is old, and used to be more common. When it originated, the phrase was natural and even sensible. It was a way to express uncertainty in unusual events. It was not taken nearly as literally as we, in our hyper-numeric age, take it.

All it meant was "This is a big flood. Don't get these very often. Maybe once a century."

The speaker's mind was also not addled by thoughts of "climate change" and the expectation that large floods must necessarily become more common because of the evils of men.

Why, incidentally, should floods become more, instead of less, common in a changing climate? There is only one answer to that.

Stop me if you've heard this one before, but there is no such thing as probability. It doesn't exist: it isn't alive: it is not a substance. Which is why there can be no such things as hundred year floods.

Probability is instead a measure of uncertainty of a proposition given some set of premises which must be specified. Different premises give different probabilities.

Pick as a proposition, "Flood of a large size this year", where "large" is known to speaker and listener, and where the locality of the flood, its geographic extent, I mean, is also understood. Then you might gather premises that allow you, conditional on them, to quantify the uncertainty of this flood.

Say this quantification is 0.01, or 1%. That's per year. Inverting that gives a "100 year flood."

Easy, yes?

Only it's not, because there are no fixed premises. Floods have causes. If we knew all the causes, and could with no error project them, then we'd know with certainty whether this flood will occur this year in this place or not.

If we don't know the causes, we have to correlate. And we all know that correlation isn't causation. Unless, of course, it's your correlation. Then you're happy to forget you knew. Thus does over-certainty grow.

Which exact correlates must we use to calculate the probability of our flood? There aren't any. Let me repeat that: there aren't any.

That means opinions can differ about the probability of the flood, because opinions differ over what best correlates (premises) to use.

Naturally, those touting global warming will include premises that insist floods must increase. Their probabilities will therefore necessarily be larger. It would not be a "discovery" that floods will increase: it was a premise. All models, which include probability models, only say what they are told to say.

That's the best we can do about future floods: bicker over the best correlates and causes to include as premises. Then make projections and see how well these do. Problem is, large floods are rare, so it's difficult to assess how well our premises (i.e. model) did in forecasting it.

We can do much better with the past. Ignoring measurement error, which is larger the further one goes back in time---remember, people weren't as numerically obsessed as we are---we can at least see how many floods of a certain size there were. This becomes exceedingly difficult with large floods, because they are rarer.

Plus, we not only have to consider the floods themselves, but the changing reactions to them. People build against now better than before, etc.

Anyway, with all that said, there isn't much going on with floods. I have some statistics quoted on this in two papers I did for the Global Warming Policy Foundation: this and even more in this. Quoting from the second:

A paper in Nature Communications helps us. It is 'Trends in flood losses in Europe over the past 150 years', by Dominik Paprotny and others, published in 2018. The authors calculate that floods in Europe killed about 21,000 people between 1870 and 1899. That fell to about 14,000 dead between 1900 and 1929, 12,000 in 1930–1959, about 6,000 in 1960–1989, and just over 2,000 between 1990 and 2016. This is an unambiguous improvement in climate-related fatalities. But it’s even better than it seems, because before 1900 there were fewer than 300 million people in Europe, and there are 746 million now. That means the rate of fatalities has not just fallen, it has, remarkably, plunged. As more people live in the same space, fewer in total and in proportion are dying from floods.

Also look to "A critical assessment of extreme events trends in times of global warming" by Gianluca Alimonti and others. They say:

This article reviews recent bibliography on time series of some extreme weather events and related response indicators in order to understand whether an increase in intensity and/or frequency is detectable...The analysis is then extended to some global response indicators of extreme meteorological events, namely natural disasters, floods, droughts... None of these response indicators show a clear positive trend of extreme events. In conclusion on the basis of observational data, the climate crisis that, according to many sources, we are experiencing today, is not evident yet.

You have to love that "yet". Saves them from being canceled.

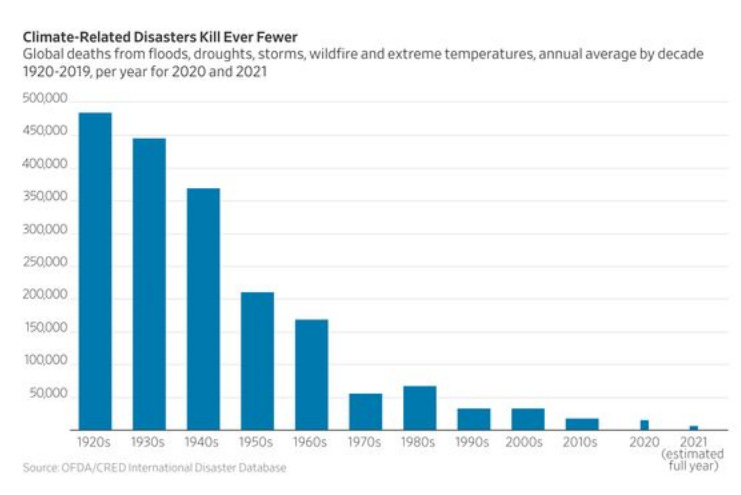

A popular source is Bjorn Lomborg's "We’re Safer From Climate Disasters Than Ever Before". He concludes, "Though it receives little mention from activists or the media, weather-related deaths have fallen dramatically." Here's his picture:

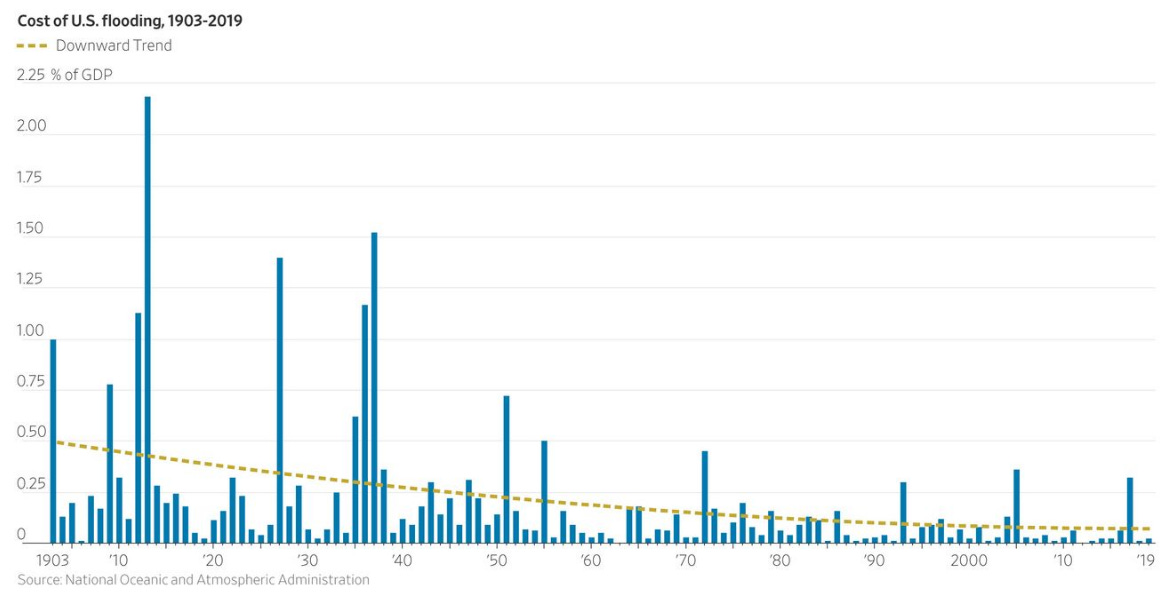

But as this series explained in regard to flood costs, only measuring the total damage of natural disasters over time misses the important point—there’s much more stuff to damage today than there was several decades ago.

As the world has gotten richer and its population has grown, the number and quality of structures in the path of floods, fires, and hurricanes have risen. If you remove this variable by looking at damage as a percent of gross domestic product, it actually paints an optimistic picture. The trend of weather-related damages from 1990 to 2020 declined from 0.26% of global GDP to 0.18%. A landmark study shows this has been the trend for poor and rich countries alike, regardless of the types of disaster. Economic growth and innovation have insulated all sorts of people from floods, droughts, wind, heat and cold.

Here's the article Lomborg refers to: "The World Is Getting Safer From Floods".

Though it hasn’t been well publicized, the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says it has “low confidence in the human influence on the changes in high river flows on the global scale.” It expects more areas will see the frequency of floods go up than go down—a negative impact of climate change, but one that’s much less dramatic than media coverage might suggest. And as the world grows richer, infrastructure and technology are likely to drive down relative flooding costs and deaths. The data show they already are.

You get the idea. No reason to panic.

Buy my new book and learn to argue against the regime: Everything You Believe Is Wrong.

Visit wmbriggs.com.

Great explanation so the folks can finally understand why we keep getting 100-year events every 6-8 years.

Also (touched on at the end) is why insurance losses are getting bigger and bigger. well, if a Hurricane hits an undeveloped coast and nobody was there, was it really ever a storm? Otoh, if a Hurricane hits a new development on the Outer Banks and 96 new homes get turned into firewood, then "Billion dollar losses from Hurricane William" will be the headline.

I think that when people talk about 100-year floods they are abusing terminology. In urban planning 100-year flood line maps are used to indicate the risk of flooding of specific properties, given specific precipitation levels. The rise of running water levels, ie, runoff, during a rain storm, in an urban environment depends on the precipitation on given areas, as well as the paving of those areas. By paving I mean any structure that does not absorb water, eg, rocky outcrops, roofs, roads, parking lots, paved lots, etc. The paving in an urban area usually increases as an area is developed. Often the storm water drainage system is not adapted to accommodate the expected increase in runoff due to new buildings, and roads. Its become popular to blame the resultant increase in the risk of flooding on global warming, which is of course incorrect. The lax management of the built environment is to blame.