Science, Non-science & Propaganda -- Guest Post by Johan Eddebo

“I Believe in Science. Trust the science. Follow the Science.”

Oh Science, glorious benefactor of the dutiful citizen who humbly recognizes his own insufficiency and weakness in light of the magnificent power and knowledge of your great machinery of truth and progress, lead us into Abundance and Safety.

Let the decrees of your enlightened experts and the intercession of your benevolent managers banish from our trustful and contrite hearts any conceited presumption of our own competence and rational sovereignty.

Discipline us that we may more fully submit to your ever-evolving omniscience, edify us that we may continually work towards uniting our wills with your eternal quest for material perfection, and inspire us to help bring about the final subjugation of the entire cosmos under the dominion of instrumental reason and its all-penetrating gaze.

All of three years ago, before phenomena like Thunberg and the COVID-event, one would have thought a tirade like this a bit hyperbolic, if accurate to an extent. That’s not really the case anymore. In today’s media climate, science is increasingly characterized in terms of myth and legend, if not a pseudo-religious morality play. To be sure, science has played a significant role in Western ideology since the Renaissance, and has arguably functioned as a cohesive myth with redemptive or eschatological trappings in the wake of religion’s retreat during the 20th century, long since pressed into service for imperial expansion and domestic legitimacy.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 is a seminal example of the popular ascendancy of this idea of science as key to the fulfillment of human destiny. Held in London during the dawn of the Victorian Era, and at the very height of the British Empire, this inaugural World’s Fair symbolically and conceptually fused together science with capital, industry and colonialism in an hitherto unprecedented manner. The emerging institution of a monolithic natural science was here spectacularly melded with the fruits of colonial exploitation and industrial technology in what was one of modern history’s most significant propaganda ceremonies.

At the behest of royalty, goods and products from all of Britain’s colonies, as well as most of the Western world, were showcased side to side with the astonishing inventions and industrial technologies of the day in more than 13,000 exhibits. The telegraph was then about a decade old, and the first undersea cable between France and England had just been laid, eventually enabling global telecommunications more than a century before the Internet. But the 1851 Exhibition already sported a fully functioning telefax machine, capable of transmitting actual images across the wire. Brady was here decorated for his daguerrotypes invented a few years earlier, and the first mechanical voting machine was also presented, providing a clear indication of the technological instrumentalization of democracy at the very outset of the spread of common suffrage.

Such marvels. Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, Michael Faraday and Samuel Colt were all in attendance at some point or other. The Queen herself made over sixty appearances at this real-life steampunk festival, and the working classes stood in awe, lining up to fund the whole ”self-financing” drama, who received more than six million paying visitors during that one summer.

The dazzling story of science wedded to power and progress is something absolutely fundamental to us moderns. It is a key pillar of not just the most dominant worldviews and ideologies, but rather a prerequisite of any acceptable consensus view of reality whatsoever. This is a situation with quite deep roots, and connects with how governance took form within the framework of early capitalism and the auxiliary ideologies thereto which developed under the auspices of Renaissance humanism and Enlightenment philosophy. Indeed, the very mechanistic reductionism that lies at the core of how our society thinks and speaks of reality itself is arguably a supportive ideology of a capitalism for whom abstract, calculable quantities, immediate utility and priceable commodities, are the central priorities.

Be that as it may, the symbolic authority of science as arbiter of truth and provider of goods, security and existential hope and fulfillment, is now the cornerstone of how we view ourselves and the world. This myth of a cohesive institution of objective knowledge that assures technological and societal progress and abundance, is really the central source of trust in our institutions, ideologies and our cultural narratives in general, having more or less entirely supplanted religious traditions in this sense.

This is one of the reasons why the invocation of science will act as such a potent force multiplier in propaganda. Science has become the fundamental meta-narrative that shapes and supplies legitimacy to almost all of our beliefs and values. It is the predominant fount of power, both epistemically, since it is taken to uniquely provide us with true beliefs, as well in its tangible promise of mastery over nature through technology.

In contrast to the Enlightenment project where reason and sensory experience, although secularized and increasingly instrumental, functioned as the basic warrant for what we can coherently hold to be true (something in principle possessed by every human being), it is now rather the infused authority of the myth and symbol of Science that reigns supreme.

While this, again, is far from a novel development, it seems to have been significantly exacerbated by the current situation. Fear and uncertainty, fomented by a global mediatic effort of almost unimaginable proportions, have driven us to embrace that which may protect us and keep us safe. Science is increasingly not just a cohesive narrative according to which we orient ourselves. It is a sacred totem upon which the fragile edifice of democracy, the rule of law and even our physical well-being is erected. The very pillar of civilization and its redemptive progress, without which all is lost.

One immediate effect of using this symbol of science as a foundation for institutional authority is that political dissent immediately becomes associated with ”denying science”. Even moderate opposition to prevailing opinions or policies then places the skeptic in conflict with the very basis of non-trivial true statements about the world around us. Since basic epistemic warrant is now authority rather than common human reason (instrumentalized or not), your arguments are almost irrelevant.

If you dissent, you’re pitting your own mere opinion against the cumulative force of the entire institution of science and its virtuous experts, who always speak with one voice, and whose collective quantity of hours of schooling and pooled knowledge naturally makes your conjectures entirely pointless. Even if the opposition also legitimately invokes science, which is nearly always the case, they are merely the heretical minority against a dominant orthodoxy supported by global mass media.

In other words, political and institutional power is rendered inviolable in being consecrated by science. This relationship is then constantly renewed through mass society’s mediatic leveraging of the core myths of modernity, something which COVID has kicked into high gear.

The thing is, all of this has very little to do with actual science, or even with the original ideals of Enlightenment rationalism. Science is at its core neither more nor less than the rational and systematic exploration of the world around us, and to enthrone it as some form of inviolable authority will immediately undermine the entire endeavour itself.

At this point, the myth’s apologists will generally maintain something to the effect that nobody has seriously claimed that science is infallible, but rather that it is a uniquely self-correcting set of methods for discerning reality. That science singularly minimizes biases, demands evidence and motivates us to seek the truth in spite of our desires and prejudices. They will generally add that science is historically unprecedented due to its “prodigious performance”. Just look at the Great Exhibition, will you?

But all of this is either trivial or false, aside from also tending to reproduce these superstitious beliefs in the near-infallibility of the institution and its representatives.

All human attempts at understanding and interacting with the world around us necessarily self-correct and demand evidence if there are any kind of stakes involved. Neanderthal seafaring 130,000 years ago was not the result of random nonsense with no method for evaluating evidence or accumulating and disseminating knowledge, and neither are the ”primitive” San people’s ways of surviving in one of the most inhospitable locations on the planet.

In terms of science’s incredible power to bring wealth, goods and contraptions to our table, its contributions should not be unduly denigrated. But certainly most fruits of industrial civilization are chiefly the products of abundant fossil fuels and the nearly free energy they provide. It is furthermore entirely possible that these boons could have been better stewarded by traditions other than modern Western science, and whether this immense growth and expansion of mankind’s disruptive interference in our natural surroundings is always "progress" can surely be debated.

Has the encroachment of modern technology upon the traditional ways of life of billions of people over the world always been desirable in the eyes of those subjected to it? Of course not. And has it always fostered the growth and maturation of knowledge rather than displacing or disrupting it? We lose ten spoken languages every year.

That science magically protects from biases is likewise contentious. If it does at all, that also goes for any tradition of knowledge addressing the threat of starvation or hypothermia. But even the best method cannot guarantee the virtue of the people supposed to put it into practice. The idea that everything society stamps with ”science” is somehow free from partiality is also clearly belied by the data on institutionalized corruption within the framework of pharmaceutical and medical research.

Leemon B. McHenry’s work, featured on Off-Guardian, is a good example. Not to speak of the plethora of science’s historical aberrations. Were the Tuskegee experiments or Nazi eugenics free from biases? Or the Scandinavian forced sterilizations which first ended in the 1970s? Sure, this is always dismissed as ”pseudoscience”, but there’s really no way to make that distinction in these cases without involving non-scientific principles or values such as justice, fairness or the right to one’s bodily integrity, which then immediately contradicts the notion of science’s unique character.

And anyhow, if pseudoscience was rampant within what everyone took to be ”normal” science just a few decades ago, well, then the point is conceded.

Science is obviously not a closed system. It must either be regarded as essentially dependent on non-science, or we must consider all forms of knowledge to be in some sense scientific and thus render the concept trivial. Fundamental principles of logic, epistemology or metaphysics are for instance entirely indispensable for any form of scientific research whatsoever. And it is impossible to even formulate research questions without regard to extra-scientific values and priorities---but these cannot even in principle be derived from empirical data on material reality mechanistically conceived.

Yet that doesn’t mean they can never be proven, or that we have no way of learning about them.

The often frantic attempts at establishing a clear and stable demarcation between science and non-science is really motivated by the need to safeguard the sanctity of a core myth of modern civilization that underpins our worldviews and almost all institutional authority.

But science was never meant to function as myth. Science was supposed to be this radical ideal of universal rationality, specifically in opposition to arbitrary authority and the fiat of princes and kings. The intention was to foster mankind’s trust in our own critical faculties. That we would develop and master these to promote a deliberate growth of common knowledge which would in the end allow us to cultivate true independence from below.

This is not the worst ideal imaginable. But these ambitions are inevitably thwarted if we set science up as some immaculate idol used and abused to develop the perceived legitimacy of our political and economic institutions.

What’s more, the positive contributions of modern science are also immediately undermined if the institution and those who lay claim to it are regarded as above reproach and interrogation. Its actual self-correcting practices will be disrupted at every level as soon as science is both regarded as a near-faultless tradition of knowledge, and captured by powerful interest groups to bolster their authority. Since science in the popular understanding is regarded precisely as a flawless way to attain truth rather than a set of infallible dogmas, this arrangement will cement all that science is taken to proclaim as inerrant in practice, while at the same time rendering every changed prediction or pronouncement equally impeccable.

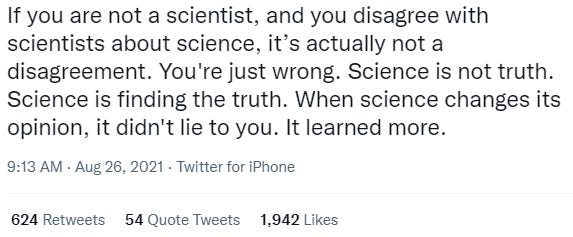

This tweet gives us a very instructive example:

”Scientists”, the elect custodians of the sacred discipline, are infallible and always in agreement. Your dissenting position, whatever it is, must be rejected by default. It doesn’t even rise to the level of an actual disagreement, because you do not have the proper authority.

It is here further emphasized that science is ”not truth”, i.e. that science as such is only the inherently superior set of methods for discovering truth, rather than some set of fixed propositions. Notwithstanding the fact that any theory or method necessarily must presuppose such a set, this focus on the excellence of the method instead of any particular information enables the last and quite disquieting statement.

Even if it actually changes its position, Science was never wrong. It just evolved according to its perfect method, extrapolating new conclusions as additional data became available. You just had an unwarranted opinion that by definition was unreasonable since it diverged from the then-current scientific consensus.

In other words, the truth is whatever Science tells you, and there are no fixed norms apart from its authority, since it better than anything else is capable of bringing us into contact with reality.

”Whatever the Party holds to be the truth, is truth.”[1]

But there’s an immediate and fatal contradiction here. Without the universal rationality and competence of the common person, there is no science whatsoever. The institution cannot possess any unique epistemic authority if this is not first found in the rational human being. If the critically thinking citizen cannot in principle discern truth by him- or herself, then neither can science.

No matter how complex this human endeavour in principle may become, it will never disconnect from the critical thinking of the common man. It can accordingly always be corrected and improved by new perspectives, analyses or questions that in principle may be posed by everyone who studies the relevant issues.

This is all the more obvious if we consider that experts in actual practice rarely are in agreement. Especially not in regard to complex issues where the data is limited or conflicting, which is almost always the case with new or developing situations. In the history of science, unanimity is many times the outcome of political decisions, common prejudices or social processes, rather than clear and unambiguous data. And time and time again, such consensus positions have turned out to be mistaken, and proven to be so by outsiders, laypeople or mavericks rather than the high-ranking experts.

For all of these reasons, it is clear that the judgments of experts, and the positions attributed to a largely fictional monolithic scientific consensus, cannot be uncritically accepted. They are in need of outside control, not only for liberty’s sake, but also to safeguard the integrity of science as such. And when it comes to truly important issues where the outcomes may be very severe and disruptive, these judgments should be examined most thoroughly, by everyone from concerned citizens and journalists to dissenting experts---even by other traditions outside of science.

The people immediately affected by the outcomes of such judgments should be allowed to ascertain whether they are truly sound, whether being established in the manner of the sciences involved really is the end of the debate, and if not other traditions of knowledge have something superior to offer. And the people making such an assessment must be afforded all the relevant data, not only soundbites filtered through a politicized mass media.

A free society can in no way submit to being governed by a cadre of unelected experts or by the powerful interest groups who employ the prestige and status of experts to cement their own authority. The judgments of specialists can naturally be valuable and useful, but they are not infallible, and they only represent one tradition among many. A free and pluralistic society must therefore scrutinize the positions attributed to the experts, especially so when they regard potentially disruptive changes to society, so that the informed self-governance of those immediately affected can be maintained. If we want to retain any vestiges of liberty in this increasingly authoritarian situation that so rapidly has emerged, there really is no other way.

We must move away from this infantilizing modern superstition, this idolized amalgamation of industry, progress and spectacular technology construed as a monolithic and infallible authority, and rediscover the rational autonomy of the common human being, the very notion from which the project of modern science once grew:

We lie in the lap of immense intelligence, which makes us receivers of its truth and organs of its activity. When we discern justice, when we discern truth, we do nothing of ourselves, but allow a passage to its beams. If we ask whence this comes, if we seek to pry into the soul that causes, all philosophy is at fault. Its presence or its absence is all we can affirm. Every man discriminates between the voluntary acts of his mind, and his involuntary perceptions, and knows that to his involuntary perceptions a perfect faith is due. He may err in the expression of them, but he knows that these things are so, like day and night, not to be disputed.

Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string. Accept the place the divine providence has found for you, the society of your contemporaries, the connection of events. Great men have always done so, and confided themselves childlike to the genius of their age, betraying their perception that the absolutely trustworthy was seated at their heart, working through their hands, predominating in all their being.

And we are now men, and must accept in the highest mind the same transcendent destiny; and not minors and invalids in a protected corner, not cowards fleeing before a revolution, but guides, redeemers, and benefactors, obeying the Almighty effort, and advancing on Chaos and the Dark.[2]

I do not believe that science is infallible or beyond reproach. As it stands, I think it is a flawed and, in the best of times, myopic set of institutions, that have now become captured and dangerously corrupt, the misuse of which threatens our common future in many ways. All the same, I do believe in science.

I believe in the goodness and decency of human beings, and I applaud their efforts to understand and improve the world around us. I believe that kindness and beauty are ubiquitous, and are deeper and more perfect truths than anything the intellect may grasp. I believe in God, and I believe that there’s a purpose and meaning to this life that is utterly beyond our comprehension, yet that we may hope to one day enter into.

I believe that there exists an objective reality around us that we partake in and have immediate access to, even if we may never fully grasp more than a minuscule part of it. And I believe that the universal ingenuity and shrewdness of human beings allow us to discover and interact with it in always new and unexpected ways.

I believe that there is truth and untruth, that two and two make four, and that from these principles, everything else follows.

So yes, I believe in science.

But I will not kiss your flag.[3]

Johan Eddebo can also be found at the Aesthetic Resistance podcast with John Steppling and others.

Footnotes

George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four, 1949. ?

Ralph Waldo Emerson, ”Self-Reliance”, in Essays by Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1841. ?

E. E. Cummings, ”i sing of Olaf glad and big”, 1931. ?

Subscribe or donate to support this site and its wholly independent host using credit card or PayPal click here