Reader Question: Probability is not real in the sense that real life things are real

Anon writes:

Mr. Briggs,

I am trying to understand the statement in the title.

It [probability] is a measure of uncertainty. It is a measure of what we know or do not know. It is epistemic, not ontic. We are saying something about ourselves or our own knowledge, not something about the world.

It is more like saying an argument is sound and valid than saying anything about reality itself.

But I come back to games of chance and the idea that there is a kind of probability built into them that influences their outcomes.

Is not the world something like this, too? Where the way it is can lead to different results and a real probability might exist in the sense that there is a 1/4 chance of x and a 3/4 chance of y in certain real situations so that if we knew everything, we would still not know whether the 1/4 or 3/4 would come back?

And yet this idea that if we really knew everything we would not need probability has power.

I am not sure.

I did just read your very good article on p values and that is wonderfully helpful. I had read a book called Stats.con years ago, where the author suggested statisticians did not themselves understand p values and the author did not seem sure there was a valid definition, if I remember correctly (not wanting to mis-represent him).

I will continue to work on this.

Something near to this pops up, too. Chance is not a cause. I agree. That is a concept, not an agent.

But is there not some chance involved in some way in terms of causal lines intersecting or are we to say there was an agent or cause behind all of that, too?

And, if life has real probability built into it the way a game of chance is set up, there would need to be some sense in which chance is a reason for results or outcomes, even if it could not be a cause or agent.

Or, maybe I am still in the dark, trying to find my way?

Could you toss anything my way or recommend anything further?

Thanks,

[Anon]

Random, and its synonym chance, only means unknown. As in unknown cause. That’s it, nothing more.

Take a game of “chance” like poker. The cards are riffled shuffled once—and stop right there.

Now my old advisor Persi Diaconis proved that if you do just one riffle shuffle, and you know where the cards in the deck started, you know where they end, too. This is easy enough to see, too. The shuffling only interleaves the cards, leaving the order of the shuffled halves untouched.

This makes it easy to guess who has what cards, if they are dealt after only one shuffle. What’s surprising is that if you do this six or fewer times, you could pull off some astonishing magic tricks. (Here’s a pdf which explains all.)

Because you are taking the known properties of riffle shuffling, and what can be deduced from that, the whole becomes more known, i.e. less random.

So, to those who know the trick, the order is not unknown, and therefore not “random”.

Same kind of thing fools people about the so-called Monty Hall problem. Turns out people turn a blind eye to relevant information, or don’t even know it’s there. And some can be become downright surly when you point out what they don’t want to see.

Other things, like dice throws, are similar. Turns out the causes of what side is face up are many, so many it’s hard to control throws, and therefore exceedingly difficult to predict. But it can be done, say, with enormously sophisticated measurements of the initial conditions of the throw and so on, and some subtle physics. That transforms the “random” to known.

Same is true everywhere. It’s just that some things, like quantum mechanics, no one knows what causes are there. Or, that is, not all the time. But things are changing even in that quarter, because some people are allowing themselves to consider the information that they didn’t at first see, or acknowledge. Sort of a grand Monty Hall elevation.

Now to your more subtle question, repeated here: “But is there not some chance involved in some way in terms of causal lines intersecting or are we to say there was an agent or cause behind all of that, too?”

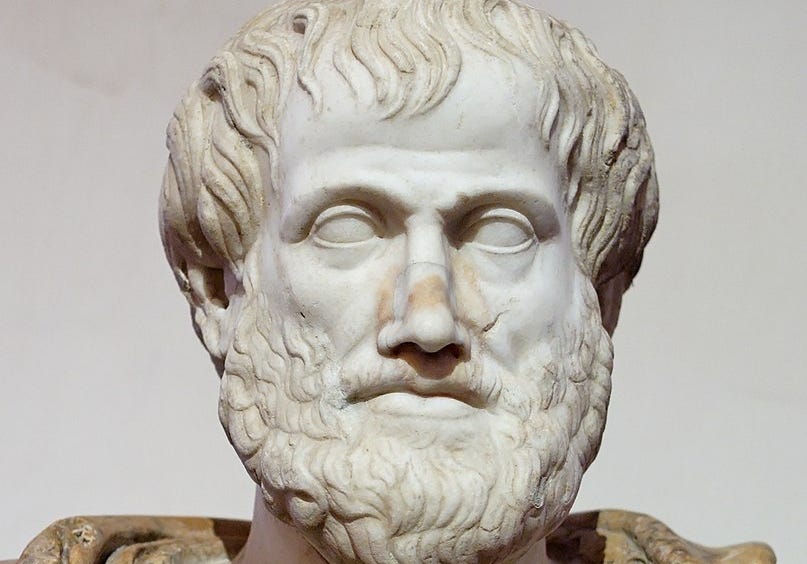

Let me answer by quoting from St Thomas Aquinas, who in turn quotes The Philosopher (as they called him), i.e. Aristotle.

11 But this way of arguing, as Aristotle says in Physics [II, 4], was used by some of the ancients who denied chance and fortune on the basis of the view that there is a definite cause for every effect. If the cause be granted, then the effect must be granted. Thus, since everything occurs by necessity, there is nothing fortuitous or by chance.

12 He answers this argument, in Metaphysics VI [2-3], by denying two propositions which the argument uses. One of these is: “if any cause be granted, it is necessary to grant its effect.”

Indeed, this is not necessary in the case of all causes, for a certain cause, though it may be the direct, proper and sufficient cause of a given effect, may be hindered by the interference of another cause so that the effect does not result.

The second proposition that he denies is: “not everything that exists in any way at all has a direct cause, but only those things that exist of themselves; on the other hand, things that exist accidentally have no cause.”

For instance, there is a cause within a man for the fact that he is musical, but there is no cause for the fact that he is at once white and musical. As a matter of fact, whenever plural things occur together because of some cause they are related to each other as a result of that cause, but whenever they occur by accident they are not so related to each other. So, they do not occur as a result of a cause acting directly; their occurrence is only accidental. For instance, it is an accident to the teacher of music that he teaches a white man; indeed, it is quite apart from his intention; rather, he intends to teach someone who is capable of learning the subject.

13 And thus, given a certain effect, we will say that it had a cause from which it did not necessarily follow, since it could have been hindered by some other accidentally conflicting cause. And even though it be possible to trace this conflicting cause back to a higher cause, it is not possible to trace this conflict, which is a hindrance, back to any cause. Thus, it cannot be said that the hindrance of this or that effect proceeds from a celestial source. Hence, we should not say that the effects of celestial bodies come about in these lower bodies as a result of necessity.

And here is another article, exploring all these in more depth. And here is another on Aristotle and chance.

There is still the idea of coincidence—-two more more incidents occurring together or in some kind of sequence, in which it appears, or there is, direction. That is to say, a master cause.

Here proof often escapes us, and we have to rely on faith or weaker forms of induction.

Buy my new book and learn to argue against the regime: Everything You Believe Is Wrong.