Repeat after me: all models only say what they are told to say.

An incredible result, says the mayor of London. Let's see how this incredible result came to be. From a news story:

Junk food advertising restrictions on Transport for London (TfL) networks have prevented almost 100,000 obesity cases, research suggests.

The advertising policy, which has been in place since 2019, could save the NHS more than 200 million, researchers claim.

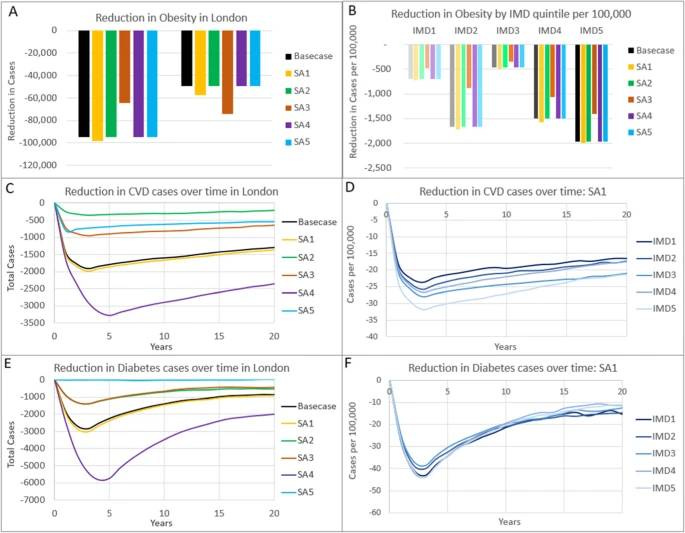

They estimate the policy has directly led to 94,867 fewer cases of obesity than expected (a 4.8 per cent decrease), 2,857 fewer cases of diabetes, and 1,915 fewer cases of cardiovascular disease.

Interesting they call these "obesity cases". Cases. Let that pass and note that this is 94,867 fewer cases, and not 94,866, as some sources earlier reported.

The peer-reviewed paper is "The health, cost and equity impacts of restrictions on the advertisement of high fat, salt and sugar products across the transport for London network: a health economic modelling study" by Chloe Thomas and others in the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity.

The Abstract begins with this sentence, starting off on a false footing: "Policies aimed at restricting the marketing of high fat, salt and sugar products have been proposed as one way of improving population diet and reducing obesity."

Eliminate processed sugar if you like, but decreasing fat is the opposite of "solving" (notice how we're always discussing government "solutions"?) the problem of too many fat people.

Never mind that. Here's what they did.

In 2019, Transport for London implemented advertising restrictions on high fat, salt and sugar products. A controlled interrupted time-series analysis comparing London with a north of England control, suggested that the advertising restrictions had resulted in a reduction in household energy [calories] purchases.

Now, most don't know this, but London is a huge heterogeneous city, and the north of England, north of a land called Yorkshire, is not much like London at all. For instance, in Yorkshire they speak mainly English. Comparing the two areas is thus likely to confirm the two areas aren't the same.

Here are their Methods:

A diabetes prevention microsimulation model was modified to incorporate the London population and Transport for London advertising intervention. Conversion of calorie to body mass index reduction was mediated through an approximation of a mathematical model estimating weight loss. Outcomes gathered included incremental obesity, long-term diabetes and cardiovascular disease events, quality-adjusted life years, healthcare costs saved and net monetary benefit. Slope index of inequality was calculated for proportion of people with obesity across socioeconomic groups to assess equity impacts.

A microsimulation model. Maybe this microsimulation had something to do with wee p-values? Too good to check.

Anyway, they stopped showing forbidden ads about bad foods in one location. Who noticed? Who knows. But

The study [by a survey firm] found that purchases of HFSS [government-defined bad] food increased over time in both locations. However; following the TfL intervention in London, relative purchases of energy decreased by an average of 1,001 (95% CI: 456 to 1,546) calories per household each week compared to the counterfactual, which was constructed using the pre-intervention trend in London and incorporating the changes seen in the North of England (to account for seasonal and secular changes common to both areas).

See that? Models of models of models. Based on sketchy data---the food bought was determined by food-recall surveys. All of which conclude what was desired: that the lack of ads caused people to buy less of certain foods.

And even if it's all fine, which it isn't, that's a thousand calories less per household each week, which is to say on average 143 or so calories a day, per household. I don't know how many are in an average household, but suppose it's 3. Then you have about 50 calories of the "bad" food reduced per person. Plus or minus. How much more in calories people got from non-government defined "bad" food we don't know.

An extra 50 calories a day---a cookie?---isn't going to cause obesity, especially from only eliminating "bad" food ads in train stations.

And we don't know what people ate, only what they bought. Our authors solve this by assuming "that reductions in weekly calorie purchase could be directly equated with reductions in weekly calorie consumption". (I did the calculation above without having read the whole paper: when I did, I was happy to discover the authors came to an estimate of 55 calories per day.)

To determine eliminating the cookie is going to prevent obesity requires yet another model. And to determine that reduced obesity leads to fewer cases of diabetes and heart disease requires other models.

This paper is therefore a modelapalooza. All in service of providing rulers with The Science they need to justify their policies.

Buy my new book and learn to argue against the regime: Everything You Believe Is Wrong.

Visit wmbriggs.com.

This is the dietary equivalent of the notorious Ferguson Coronadoom simulations of two and a half years ago. The former led to masks and lockdowns for everyone but London's "master of disaster", his mistress and a now former Prime Minister. The latter is going to be used to force us to eat gruel and then bugs and eventually each other.

Just saying the journal's name out loud once a day will take 50 calories.