Breaking: Wind From Tropical Cyclones Cure Hemorrhoids

Lost count of the number of "studies" that feel---not think---that they must invoke terror to justify their undertaking. Take this peer-reviewed gem from Nature Communications by Robbie M. Parks and a slew of others: "Tropical cyclone exposure is associated with increased hospitalization rates in older adults".

"The intensity of tropical cyclones is predicted to..." Predicted to. How about some Reality instead of predictions?

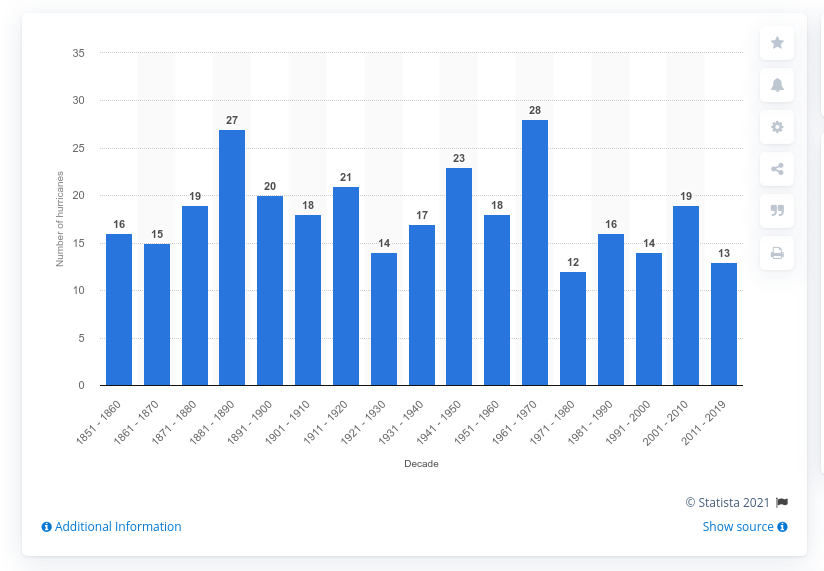

Such as the number of actual hurricanes hitting land:

"Say, Briggs, why don't you point to an official source, like NOAA?"

Because that bureaucracy has so far only counted up to 2004. We wouldn't want to rush them.

Never mind all that. Let's focus on this paper, for it is an excellent example of the depressing practice of releasing models fits, and the sad reliance on p-values. Except for the opening, it's a mostly harmless paper, too. It concludes people are more likely to be injured during and right after a storm than before it, which the authors say is good for hospital planning. Both statements are surely true; neither is a surprise.

They counted Medicare hospitalizations, and only those, for places that had "at least one tropical cyclone during our 16-year study period". They looked from 0 days (the day storms hit) and up to 7 and not 8 days after, because why not.

Here's their big finding:

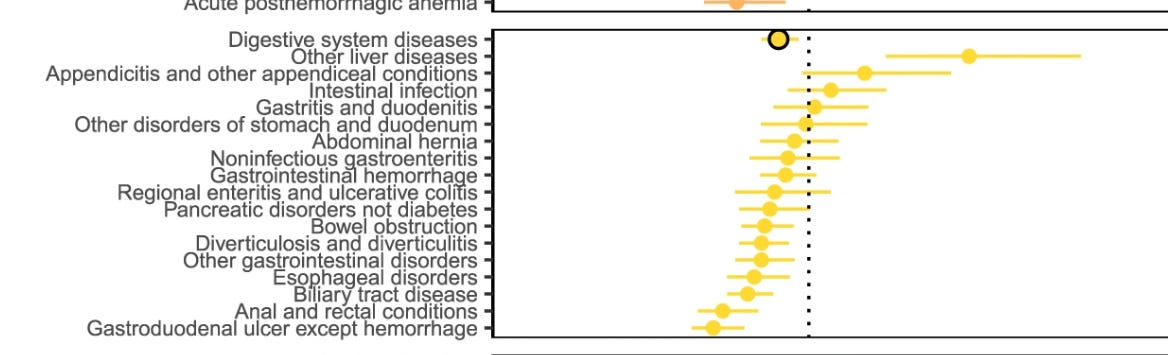

In Fig. 4, we present average relative (percentage) changes in hospitalization rates across the eight examined lag days across the 13 causes in the main analysis, as well as for sub-causes with at least 50,000 hospitalizations during our study period. The sub-causes are linked to the 13 main causes in Supplementary Table 2. Respiratory diseases exhibited the largest average increase in hospitalizations (14.2%; 95% CI: 10.9, 17.9%). We observed the largest decreases in hospitalization rates for cancers (4.4%; 95% CI: 2.9, 5.8%).

All right. Here's a closer picture of some of those sub-causes:

The vertical dashed line is 0% change: to the right are increases in hospitalizations in the 0-7 days after a cyclone hits, and to the left are DECREASES. In other words, if tropical cyclones can cause increases in hospitalizations, they can also cause decreases.

We're doing science here. Because it is science, the authors have proved, using wee p-values and a convoluted model, tropical cyclones cure "Anal and rectal conditions" and "Bowel obstructions". Also "Hemorrhoids."

Must be those fresh breezes.

Look. If you take any event, cyclone or cheerleading practice dates or whatever, and look before and after that date, and then order hospitalizations by increases and decreases about that event date, a certain order in diseases will always appear. After all, some disease has to come first and some last. Because you have an n of 70 million, you are guaranteed to get wee p-values, or, their equivalent, small confidence intervals.

You will certainly get an order of diseases, from decreases to increases, but this is no proof, no proof whatsoever, that the event you picked caused the decreases and increases. There is no proof the event caused some diseases to grow worse and some better, so that hospitalizations would decrease or increase.

This is obvious, no?

If it isn't obvious, you are left with bizarre interpretation that tropical cyclones cure hemorrhoids. That cyclones can exacerbate asthma (another result) is plausible, but then we didn't need a "study" to prove it. But if cyclones can cause asthma, then it must also be true that they alleviate breast cancer. Both "results" are reported here.

Or how about this, a limitation which the authors later acknowledge. During storms people don't go to the doctors unless it's an emergency, like for injuries---and we see injuries are on the increases side of the plots. On the other hand, during hurricanes and the like people stay home and wait for the hospitals to clear out to have their hemorrhoids lanced and prostates fingered---and these decreases are also "discovered".

But you'd get the same kind of results for any date you picked with an n this size. It might not be the same order, but there'd be some order, and you'd have the overwhelming temptation to conclude the event you picked caused the order. That's what they did for cyclones. If it's a legal statistical move for that event, it is for any.

Which is backhanded proof (as if we needed more) that probability models can't prove cause. The authors would have been better off releasing a predictive model saying "Here's how many vacation days proctologists can take when a storm is expected" and the like.

Add to all this the epidemiologist fallacy: we never know the actual cyclone "exposure" of anybody. It's all a guess, which the authors admit. But they still claim "Any resulting bias" is in their favor.

Don't use p-values or confidence intervals. Report predictive models instead.

Subscribe or donate to support this site and its wholly independent host using credit card or PayPal click here